Not sure how to explain this one. Just got word that the Lackawanna County Library System cancelled my appearance at the Scranton Cultural Center that was scheduled for June 23. A curt email was sent to my assistant Donna informing her, without explanation, that I was not welcome. When she asked for a reason, she was given a somewhat bizarre excuse complaining that I made a few other stops in the region. This wasn't the first time a local appearance in the Scranton-area was mysteriously cancelled. The first was back in October when WVIA TV cancelled a scheduled one hour live program just a week after receiving the book (that sorry story is explained a few posts down). The West Pittston library was excited when I agreed to a fundraiser in December at a local Catholic Church only to get the word that some other unplanned event had taken precedence (Bingo?). But I have to say the recent cancellation by the folks at the Lackawanna County Library System was the most surprising, and disappointing. Interest in The Quiet Don in the Scranton/Wilkes Barre area has been overwhelming. Its been the Number One non-fiction book within the entire library system since it was published Oct. 1, besting authors including Bill O'Reilly and John Grisham (I've never been able to say that before). We've since received more requests for speaking/book signings than I can count (including schools, colleges, book clubs and local companies). So we decided to make just six select appearances throughout the entire region over a four month period. One was in Hazleton in March at Penn State University, another in the Poconos, two in Wilkes Barre and two in Scranton. The first Scranton appearance was in April at Marywood University. Aside from being very well attended, it was notable for the sudden appearance of fire trucks responding to an anonymous call about a fire inside the building where I was to speak (turns out the room with the supposed fire didn't even exist). The second Scranton discussion/signing (and final appearance) was to be June 23 at the Cultural Center. Mary Garm, the library administrator, traded numerous emails with my assistant Donna scheduling the appearance, which was the only one scheduled for June. Aside from a Powerpoint presentation, we were planning on promoting it in tandem with the upcoming "Who Killed Jimmy Hoffa?" program that PBS is scheduled to air July 22 on its popular History Detectives series. I consulted on the program as well as interviewed for it at a local restuarant last summer. But Garm sent a terse email last week suddenlty cancelling the event, no explanation given. And this was a day after we received our check. So, in a first for me, I'm getting paid not to speak. I was mildly amused when told of the email. But I learned later that the library staff was telling its patrons that I had cancelled due to a prior committment. And that's when I got angry. It's bad enough that a library of all places allowed some arm twisting from an unhappy sponsor, board member, politician or others (take your pick) to stifle a free form discussion about a subject so close to so many in that region. But to blame it on me? Shame on you. I emailed Garm demanding an apology. All I got was a response saying it was a mixup. I'm sure there's more to this and the real reasons will eventually surface. That said, if clearer heads at the Lackawanna County Library System decide to reverse course and right this wrong, feel free to give me a call. I'd be more than happy to come to Scranton to discuss this remarkable story. After all, you did pay me.

8 Comments

This was published on www.pennlive.com on Oct. 22

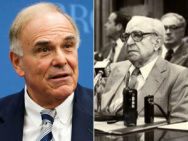

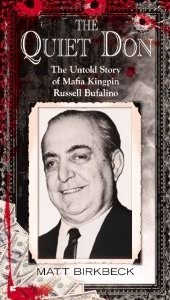

Chief Justice Castille still has some explaining to do: Matt Birkbeck On Oct. 9, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court issued a rare statement calling into question claims made in my book, The Quiet Don. Released by Penguin on Oct. 1, the book reported, among other things, that the court intentionally interfered in the prosecution of businessman Louis DeNaples and his priest, Rev. Joseph Sica, for lying to a grand jury about their alleged ties to Mafia leader Russell Bufalino. The grand jury had been impaneled to determine if DeNaples lied to the state gaming board about his alleged mob ties to obtain a gaming license for his Mount Airy Casino. The court’s interference, which delayed the prosecution for a year, frustrated law enforcement officials to the point where Dauphin County District Attorney Ed Marsico finally agreed to drop the charges in return for Mr. DeNaples giving up ownership of the casino. Chief Justice Ronald Castille took issue with that narrative, saying the book contained a “misleading and incomplete portrayal” of the courts actions. “The book in question provides a well-known account of a northeast Pennsylvania crime syndicate, but also attempts to weave assertions of impropriety on the part of this court that are not remotely supported by facts,” Chief Justice Castille said. “There is no doubt that Mr. Birkbeck failed to fully research and understand the legal process about which he writes. Consequently, his narrative falls so far short of a complete story as to merit comment.” But Castille did comment further, writing that the court intervened on behalf of DeNaples to address accusations by DeNaples’ attorneys of so-called “grand jury leaks” to the press that covered the prosecution. “There was nothing extraordinary in the Supreme Court’s actions in agreeing to consider the petition,” wrote Castille. “Staying a lower court’s orders is a normal procedure when the Court considers a petition and the Court has exclusive direct review responsibility over Grand Jury issues.” What Castille failed to say is that the court rarely ever intervenes in a grand jury investigation. In the DeNaples case, his court intervened not once, but twice. And that intervention had a profound effect on the DeNaples’ prosecution, freezing the investigation for over a year. And for good reason: Mr. Marsico planned to have William D’Elia testify at DeNaples’ preliminary hearing. As I report in the book, D’Elia assumed the leadership of the Bufalino crime family after Bufalino died in 1994 and had agreed to cooperate with federal prosecutors after he was charged in 2006 with conspiring to kill a witness and launder drug money. D’Elia subsequently testified before the state grand jury investigating DeNaples and he told me later, through his attorney, what he told the grand jury: That he had a 30-year business and personal relationship with Mr. DeNaples. D’Elia was prepared to testify to that relationship in open court, testimony that would have been devastating to Mr. DeNaples and to his many supporters, which included several state legislators and former Gov. Ed Rendell. (“I happen to know Mr. DeNaples, and know him well,” said Rendell after the charges against DeNaples were dropped). Perhaps most interesting, Castille’s narrow explanation didn’t in any way refute the thrust of the narrative, which had been culled from interviews with, among others, senior law enforcement officials involved in the DeNaples prosecution: The Supreme Court participated in a conspiracy with Rendell, several state legislators and the state gaming board to get DeNaples’ his gaming license. Castille ended his letter, which is posted on the courts website, by writing that, “Facts matter and misinterpretation of facts can be damaging to the trust that is necessary to sustain our court system. As the response details, this court’s handling of cases in question was nothing but straight forward.” I would suggest that the court’s actions in DeNaples case and the entire gaming fiasco was anything but “straight forward,” and that Justice Castille has a lot more explaining to do to earn the trust that he correctly says is necessary to sustain our court system. Matt Birkbeck is an author and journalist.  (For those who may have missed this, the Associated Press ran a piece on The Quiet Don). By Michael Rubinkam EASTON, Pa. (AP) — Pennsylvania state police ran a top-secret investigation into whether then-Gov. Ed Rendell and his administration rigged the outcome of the casino licensing process to benefit favored applicants, including a wealthy and politically connected businessman suspected of having mob ties, a new book asserts. But the probe failed to lead to criminal charges against anyone in the administration or on the state gambling board, and prosecutors blamed the state Supreme Court for thwarting the investigation, according to "The Quiet Don," a forthcoming book by Matt Birkbeck that also serves as the first full-length biography of reclusive northeastern Pennsylvania mob boss Russell Bufalino. Birkbeck covered the troubled beginnings of Pennsylvania's casino industry as a newspaper reporter, and here he pieces together the yearslong effort by state police and local prosecutors to probe whether corruption was involved in the awarding of the lucrative casino licenses. The narrative emerges from interviews with dozens of participants, including now-retired Lt. Col. Ralph Periandi, the No. 2 official in the Pennsylvania State Police. Periandi initiated the probe in 2005 because he suspected that "Rendell, members of his administration and others in state government might be trying to control the new gaming industry in Pennsylvania," Birkbeck writes. Rendell did not return a call for comment. He has long denied any impropriety. The book follows Periandi and his small, secret "Black Ops" team of covert investigators as they dig into the gambling board, the Rendell administration and Louis DeNaples, a powerful northeastern Pennsylvania businessman who'd been awarded a casino license despite questions about his suitability. DeNaples was eventually charged with perjury in January 2008 for allegedly lying to state gambling regulators about whether he had connections to Bufalino — the titular "quiet don" — and other mob figures. Prosecutors later dropped the charges in an agreement that required DeNaples to turn over Mount Airy Casino Resort to his daughter. DeNaples has long denied any ties to the mob. Dauphin County District Attorney Ed Marsico agreed to the DeNaples deal because "the Supreme Court had interfered in his case twice already, and he feared that no matter what he did, the court would see to it that the DeNaples prosecution would never move forward," Birkbeck writes. The author said investigators "basically stepped on a bee's nest" when they went after DeNaples. Chief Justice Ronald Castille did not return a call placed to his office. He has rejected similar allegations about Supreme Court interference in the gambling industry as ludicrous, slanderous and irresponsible. "The Quiet Don" traces Bufalino's ascent to mob boss, including his role in organizing the infamous 1957 meeting of Mafia leaders in Apalachin, N.Y., his control of the garment industry in New York and Philadelphia, and his control of the Teamsters union and its leader, Jimmy Hoffa. The book asserts that it was Bufalino who ordered a hit on Hoffa, a claim also made in the 2004 Mafia memoir "I Heard You Paint Houses," in which confessed mob hitman Frank Sheeran said he killed Hoffa on Bufalino's say-so. Hoffa disappeared in 1975; his body has never been found. What's new here is the reason: Birkbeck writes Bufalino was upset by a 1975 Time magazine article that linked him, for the first time, to the CIA's attempts to enlist the Mafia to kill Cuban leader Fidel Castro, and he feared Hoffa would tell Senate investigators what he knew about the failed plot. It's been several years in the making, but my book on Russell Bufalino will finally see the light of day on October 1. The Quiet Don is actually two stories, one about a modern day corruption investigation involving the highest levels of government, and the other the nuts and bolts (an astonishing) look into the life of the man who was arguably one of the most powerful mobsters in the U.S. We're still four months away so I can't give away too much suffice to say any student of organized crime, U.S. history and high level political corruption should put The Quiet Don on their fall reading list.

|

Matt Birkbeck's Blogspot

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed